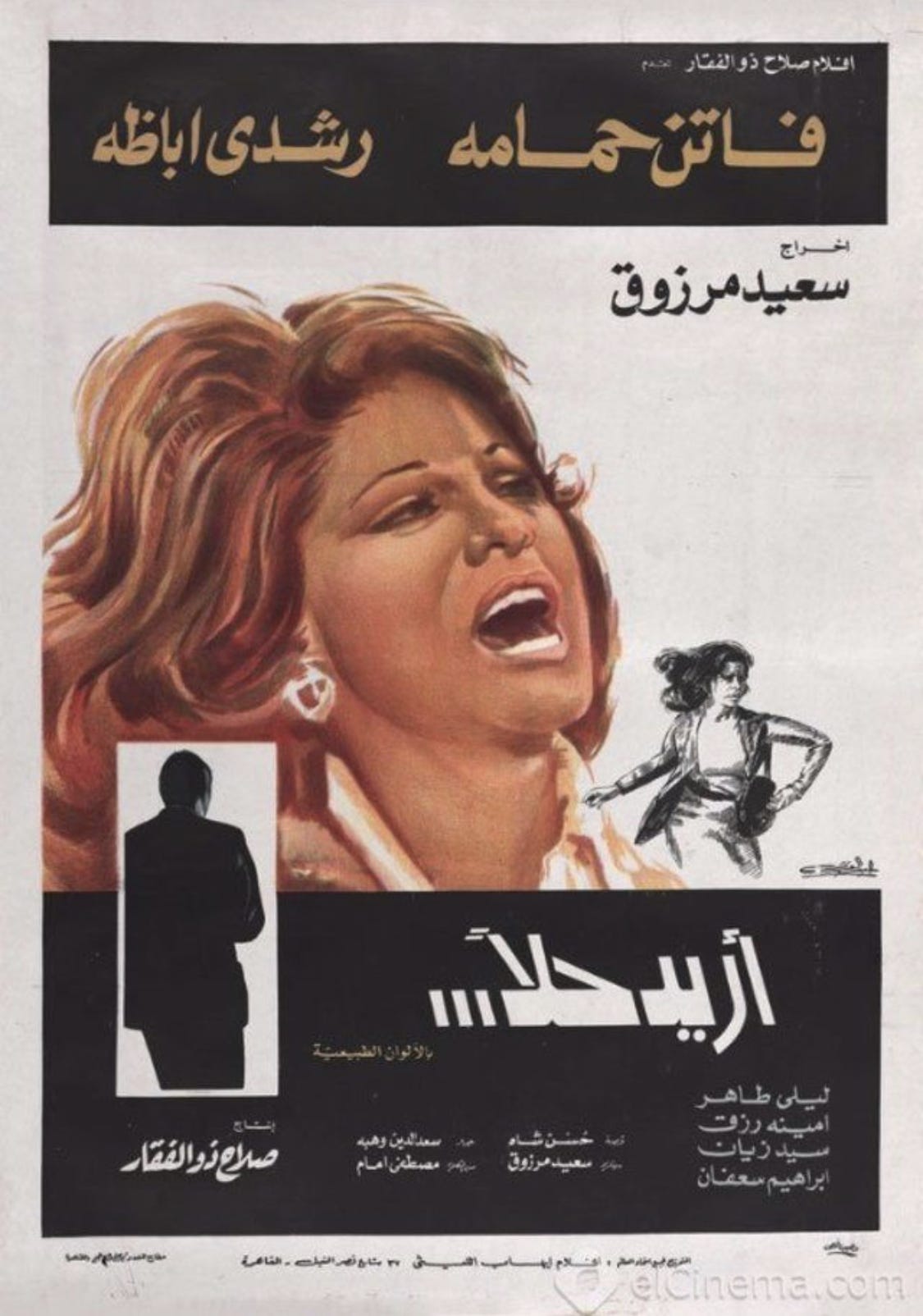

'Orid Hallan' Shows Us How Good a Divorce Can Be

Rich coming from a woman who's never been married

General Synopsis

The 1975 film directed by Said Marzouk follows Doria (played by Faten Hamama) seeking a khul` in 1965 as she is making trips to a chaotic family affairs court and encountering women worse off than she is and experiencing flashbacks of her own marriage to a cartoonishly sociopathic man and how she has gotten here. We see that her husband, Medhat (played by Roshdy Abaza), will verbally abuse her, drink heavily, and openly cheat on her in a negligée with a foreign woman whom he will always treat better. We know from the way he talks to her father that Medhat never wanted to marry Doria but could not commit to a foreigner to due constraints in his diplomacy job. He is arrogant, cruel, capricious, constantly on the edge of violence, and harasses Doria for her nerve to leave him. Doria, for her part, must make up for the time she lost over the course of her twenty year marriage by sacrificing her relationship with her father over her decision and the institutional incompetence that never fails to favor a man.

In meeting a woman named Hayat (played by Amina Rizk) we see the familiar story of a woman who dutifully fulfilled her role as a wife for thirty years only to be cast aside for someone younger and live out the rest of her own life on the streets. Amina Rizk, though having a few minutes of screen time, delivers a heartbreaking performance of a woman with dignified composure who never gets peace nor justice in this life. In Hayat, Doria sees a possible future of herself if she does not act in that very moment. In observing another woman who’s mechanic husband verbally divorced her and refuses to provide for his children, Doria sees a possible past if she had acted too soon and lost her own son, Karim, before he had the chance to grow up and be spared of scandal. This aggrieved stranger must give up her children because an errant child growing up with a future is better than a starved one.

To battle failings in the legal system and her husband’s egotistical stubbornness, Doria must be one step ahead of legal scholars and completely open about her struggles to have any hope of a new life for herself. Her brother, Fouad, her love interest (and foil to Medhat) Raouf, and Doria’s friends all rally behind her in the face of Medhat’s dirty tricks and an unfair cross examination. When Doria starts to live honestly and says what she needs she starts feeling hope about how the rest of her life will get better only to be thwarted at the last scene when too much time has passed due to Medhat’s stalling and she must start her case all over again after a four year process from the start of the film after a judge ruled against her trapping her in a new, but eerily familiar, abusive cycle at Medhat’s hands.

How the Film Affected Egyptian Society

The wife of Thabit b. Qays b. Shammas [Habiba] came to the Messenger of God, peace be upon him and said:

Habiba: O Messenger of God, I do not hate Thabit neither because of his faith nor his nature, except that I fear unbelief.

The Messenger of God (PBUH): Will you give back his orchard?

Habiba: Yes.

And she gave it back to him and he [the Prophet] ordered him and so he [Thabit] separated her.

- al-Bukhari 1868, 266

This one Hadith shown above is the reason why Husna Shah wrote Orid Hallan. Before for a woman to get khul`, her husband had to accept her request for a judge to approve it which is the wall that Doria keeps running up against. Over and over again she is the stereotypical wealthy, recalcitrant wife and is punished for four years of not prostrating herself unto to Medhat. To a traditionalist this is just. The framing of the situation, however, is a tragedy. The court and Medhat think that they are doing Doria a favor by denying her this divorce but in actuality this is a tragedy. It is this denial that makes Doria miserable which was the whole point of the Hadith in the first place. A marriage is not supposed to be a source of misery.

Over the course of the thirty five years it took for the khul` law to pass the debate, as detailed in Nadia Sonneveld’s book Khul` Divorce in Egypt: Public Debates, Judicial Practices, and Everyday Life, she shows just how hard women’s groups and the international community had to fight tooth and nail and strategize to get an Islamic based no-fault divorce and the abolishment of the ta`a ordinance (a law that allowed men to force women back into the marital home by means of law enforcement). It wasn’t until the government stepped in and unilaterally instituted Law no.1 of 2000, Article 20 to keep foreign revenue coming. This was the solution that everyone had to accept after years of discord. There were also concerns over a poor woman’s ability to get divorces from the screenwriter, Husna Shah and notable feminist author Nawal Saadawi but they both still noted the right direction the laws were moving in. Loud and incessant voices came resonant and alarmed with accusations of Western and Zionist conspiracies, over emotional incapacitation of women, bald faced misogyny with Egyptianized madonna/whore complexes, and power struggles over who has the moral and religious high ground were not hard to find amongst al-Azhar scholars, People’s Assembly MPs and Islamists.

Timeline of Khul` And Other Rights

1929: The institution of the Personal Status Laws formally giving men the responsibility to provide for the family and act as the head of the house. He can dictate, the marital status of the wife, her movement and her ability to work comprised of 318 clauses.

1975: Orid Hallan is released

1979: Law no. 44 grants women alimony for two years in cases of no fault attributed to her and the right to stay in the marital home with children in their custody. The same clause abolished the ta`a ordinance, allowed women another two years of alimony payments if their husbands took another wife without their permission.

1985: The High Constitutional Court rules the 1979 clause unconstitutional and therefore invalid reverting personal status laws to the original 1929 statutes.

1994: Women can choose whether or not husbands are allowed to take additional wives in their marriage contracts.

January 2000: Law no. 1 of 2000 (or The Law on Reorganization of Certain Procedures of Litigation in Personal Status Matters) expedited personal status cases and turned 318 clauses into 79, legalized `urfi divorces and Article 20 (referred to as the khul` clause) grants women a unilateral divorce after a three month waiting period, the mahr payment, the forfeiture of financial rights and the attestation that she hates her married life and is concerned on transgressing her religious limits.

May 2000: Nonproviding husbands either on alimony or child support could be sent to prison and women could include preconditions prior to a marriage.

August 2000: Women are allowed to travel unrestricted by their husbands as a constitutional right.

November 2000: Women are granted the right to renew their passport without a husband’s permission.

2004: Mothers are granted the right to pass on nationality onto their children.

October 2004: New family court system opens to streamline family law practice.

Why We Talk About Divorce Now

I will never forget growing up and seeing how my father continues to love and honor my mother. He made sure my sister and I knew that so long as a husband never takes for granted the worth of his wife then neither will be at each other’s mercy. As time goes on that nugget of wisdom has only ever been proven right. A marriage and what it’s supposed to be is nebulous in a way only because the definition has proved to be so fluid. In this context, marriage is a religious institution first that’s integrated by the state. The debate, now that “no fault” divorces are so normal, is whether or not a marriage is only supposed to be a mutually consenting contract with that consent being able to get withdrawn by either party at any time for any reason. In Islam there are various forms of marriage contracts and even more forms of divorce. To go further, any notion of a marriage being a civil contract is a nonstarter.

There is no shortage of marriages and divorces taking place in Egypt. There is also nothing short of absolute moral panic from the government who must process these divorces surrounding it. With the second highest divorce rate in the Middle East people are starting to wonder what is going on with young people. In keeping with the rest of the world, women are the ones who overwhelmingly file for a khul` because of the lower barrier to get it through a court. Domestic abuse and infidelity, though far more pervasive than what can be proven in court, is still widespread. A more self actualized, financially independent and informed woman mixed with a decreased social stigma around divorce in general means that there is an exit from a bad marriage and women are rightly not afraid to use it. The worst that will happen is that they’re single and loneliness isn’t as scary as a bad marriage that will never end. This leaves men in a position of being with partners who don’t need them as providers and a need to adapt to a new and very different set of expectations phasing out the maintenance-obedience relationship.

The Egyptian government is wondering why so many bad marriages are taking place and they have a few theories. It could be anything from financial hardship, overindulgence is vices like drugs and alcohol and poor communication. To their credit they want to make marriage counseling a common and shame-free tool in saving couples and even proposed having young couples submit to drug tests though that suggestion has little hope of ever getting passed. But if the average age of young women getting married is twenty years old it’s no surprise why these marriages are failing no matter what how frugal, how sober, how calm or how well advised someone is. This young age is not something the government is looking at as a factor. People tend to change in their twenties and they grow apart in their relationships. How can these couples get to know each other inside and out like how officials and activists are advising when twenty year olds are still in the process of determining who they even want to be?

Then we have men’s right activists wanting to do away with khul’ altogether claiming that it leaves families destroyed, robs a father of his ability to parent their children and, furthermore, opens a child’s wellbeing to the complications of their parents’ animosity. However in a forfeiture of a woman’s financial rights that a khul` stipulates, why should both parents agree to a divorce for it to be even considered? When someone files for a divorce, the reality is that pride is nowhere to be found and wounded pride is no one’s responsibility but the person who it belongs to. Immaturity and entitlement have no places in marriage. After a divorce is finalized, a man is free to remarry and go about his life as a bachelor again effectively with unfettered access to his children. It doesn’t make sense to trap women in a dysfunctional marriage to soothe a fragile ego. On the other hand, a woman has to fight an uphill battle to keep fathers current on alimony and child support payments (something we can see a dramatized glimpse of in the 2022 series Faten Amal Harby) and cannot get officially remarried without the risk of losing her children. It remains, to this day, that getting married, though a joyous occasion, poses more of a risk to woman than a man and it is not a surprise that women are wise to that.